HU/OOP Introduction

Ez a szkript tutoriál elmagyarázza, hogy mi az az objektumorientált programozás, és megtanít arra, hogy hogyan kell használni az MTA OOP funkcióit. Ezt qaisjp hozta létre (talk) 22:48, 8 June 2014 (UTC). Forum post.

Bevezetés az OOP-ba

Az OOP az az object orientated programming rövidítése. Három egyszerű szó, de valószínűleg az utolsót fogja a legjobban érteni. OOP-nak (Objektumorientált Programozásnak) nevezzük azt, amikor minden, egy objektumhoz köthető függvény az adott objektumon kerül meghívásra. Az objektum ez esetben egy osztály példánya - egy elem osztály, egy database osztály, egy játékos, egy jármű. Eredetileg minden procedurális volt, hasonlóan kellett megcsinálnia egyes scripteket:

local vehicle = createVehicle(411, 0, 0, 3) setVehicleDamageProof(vehicle, true) setElementFrozen(vehicle, true) setElementHealth(vehicle, 1000) setElementVelocity(vehicle, 0.2, 0.2, 0.2) destroyElement(vehicle)

A legtöbb esetben tudja, hogy mivel foglalkozik. A változó majdnem mindig a típushoz kapcsolódik, ezért a felrobbanó járművett ennek megfelelően nevezné el, például explodedVehicle, vagy legalábbis a szövegkörnyezetben megértené, hogy az exploded magábafoglalja a járművet amikor az az onVehicleExplode event-ben van. Ezért egy hosszú függvényt kell írnia és manuálisan kell hivatkoznia a járműre amikor procedúrálisan dolgozik. Fájdalmasan. Az objektumorientált programozás nagyon különbözik ettől, és minden egyes "objektel" együtt dolgozik. Ahelyett, hogy hívnia kellene egy funkciót, és a híváson belül kellene rá hivatkoznia, valójában az osztályon BELÜLI funkciót hívja meg.

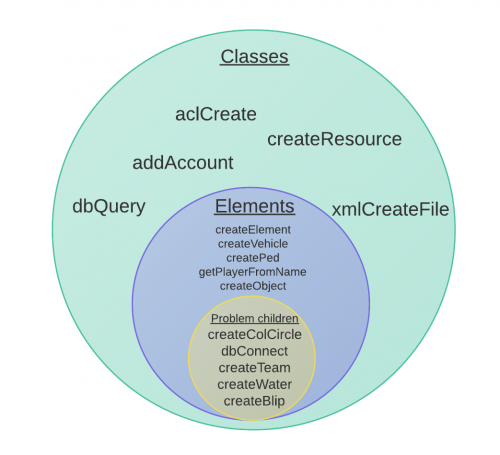

You probably think everything you can create and pass to functions are elements. A vehicle is an element. A player is an element. Anything that is an element is also a class. Connections create an instance of a class, but "connection" isn't an element, it's an instance - an object. Throughout the tutorial when I say object, I don't mean createObject (unless I actually mention it, but to make things clearer I will avoid mentioning physical objects as I write this article. Here is a fancy venn diagram I created to show the simple organisation of classes and elements.

The functions on the left are sorted to show what kind of category the returned value rests in. We've got Classes, Elements and "Problem children". Problem children aren't real categories written in the code, just functions that break rules. Everything you can play with are classes: resources, vehicles, and teams.

All elements are classes, you can do:

destroyElement(ped)

but you can't do:

destroyElement(resource)

Problem children are weird things. You can't do all the functions mentioned in (actually, all elements don't allow the full assortment of functions to be applied to them, but I've especially mentioned a few of them) in the "Element functions" section of the functions list, but you can do destroyElement() on them. There are children of classes, for example, with players, the system goes like: Element -> Ped -> Player". All Players are Peds and all Peds are Elements. Not all Peds are Players, and certainly not all Elements are Players. The main point here is that almost everything that you can create or retrieve and then reuse later use a class.

Instead of the code before, the code could be replaced with this:

local vehicle = createVehicle(411, 0, 0, 3) vehicle:setDamageProof(true) vehicle:setFrozen(true) vehicle:setHealth(1000) vehicle:setVelocity(0.2, 0.2, 0.2) vehicle:destroy()

It works pretty similar to how a table works, it's just like customTable.setSomething() except the use of : makes Lua convert customTable:setSomething() convert to customTable.setSomething(customTable). This is pretty internal stuff about syntactic sugar and you don't really need to worry much about it.

Those functions are pretty useful, but there are more changes with OOP, I'll explain this below.

Instantiation, variables

OOP removes the need to say the "create" part of the function, so instead of saying createVehicle, you just say Vehicle. It works exactly the same way, it's almost just like doing Vehicle = createVehicle. Fancy, isn't it? The only difference here is that you miss out on the extra things offered, Vehicle doesn't have these extra things, but Player definitely does. For example, instead of doing getPlayerFromName(), you would do Player.getFromName(). It's a nice and simple way to organise functions.

| Tip: Vehicle() works because it actually accesses the Vehicle.create function, this allows you to omit the .create when simply "creating an object" |

Since OOP sits on top of procedural, many things have been inherited from the style of procedural, but to make things easier we have variables for all the functions that require a single input. We've shortened getElementDimension() down to element:getDimension(), but we can also go one layer deeper: element.dimension. Yep, just like a variable. You can set this variable just like a normal variable and read from it just like a normal variable. Hey, you could even do this:

local function incrementDimension()

local player = Player.getRandom() -- get a random player

player.dimension = player.dimension + 1 -- increment dimension

end

setTimer(incrementDimension, 60*1000, 10) -- set a timer for sixty thousand milliseconds, sixty seconds, one minute

This code would take a random player and move them to the next dimension every minute for the next ten minutes.

Vectors

player.position works too! But how do you change three arguments... using one variable? Vectors. Vectors are very powerful classes and they come in multiple forms, for the purpose of this introduction I'll just cover a three dimensional vector in terms of elements. Using a vector is very simple, and is, of course, optional. Wherever you can currently use positions, you can use a vector.

So, this is a simple example of creating a vehicle and moving it to the the centre of the map using vectors

-- First, create a three-dimensional vector local position = Vector3(300, -200, 2) -- some place far away local vehicle = Vehicle(411, position) -- create a vehicle at the position vehicle.position = centreOfMap - Vector3(300, -200, 0) -- move the vehicle two units above the center of the map

Yes, I used the negative sign. Vectors aren't just fancy ways for positions or 3d rotations or whatever, you can use maths on them. The special maths hasn't been documented yet, but I'll try and work on that. So, as you can see in line one, I created a 3D vector at 300, -200, 2 and then in line two I created the vehicle at that position.

vehicle.position returned a vector and also takes a vector - it is pretty much setElementPosition() without the "()". Just a simple variable; so, in line three, I changed the vector value of the position of the vehicle. This is where the maths happened, in simple terms this is what is going on:

x = 300 - 300 y = -200 - -200 z = 2 - 0

Vector maths is slightly complicated but it definitely allows for a wide variety of mathematical magic. Check out the useful links below related to Vectors and Matrices (Matrices = plural form of Matrix) to understand more about how this works.

Understanding the documentation

The documentation for the OOP syntax intends to be very simplistic and is supported by the procedural syntax. To keep things simple, everything is consistently formatted in a certain way.

OOP Syntax Help! I don't understand this!

- Note: Set the variable to nil to execute removePedFromVehicle

- Method: ped:warpIntoVehicle(...)

- Variable: .vehicle

- Counterpart: getPedOccupiedVehicle

- Sometimes a note is added to the page. This will explain any special differences in the use of OOP for that function.

- Methods can either start like player: or Player. - the former is only for a function on an instance (setPlayerHealth) and the latter is a static method (getRandomPlayer).

- The counterpart section this allows you to see at a glance how the variable can be used. In most cases this can be inferred from the function page.

If you are a contributor to the wiki, please also consider reading the OOP template.

Useful links

Other useful OOP related pages: